The move toward purpose-driven business appears to have gathered steam over the past decade. Andrew Edgecliffe-Johnson, a columnist for the Financial Times, writes (“Beyond the bottom line: should business put purpose before profit?” January 4, 2019):

“Most of the capitalists an FT journalist meets in 2019 sound more like the protesting shirtmakers of the 1970s than the Nobel-winning economist. Over the past year I have had business leaders lament to me that no Wall Street analyst ever asks them about their efforts to tackle climate change; I have seen companies such as Merck and Johnson & Johnson remind investors that their pre-Friedman founders believed profits would only flow if they attended to other priorities first; and I have heard Unilever’s outgoing CEO Paul Polman ask provocatively: ‘Why should the citizens of this world keep companies aroundwhose sole purpose is the enrichment of a few people?’”

Investors are making their preferences heard on ESG (economic, social and governance) as well. According to the US SIF Foundation, in 2018, $12 trillion—one dollar out of every four of the $46.6 trillion in total assets under professional management—was invested in funds that seek social and environmental benefits along with financial growth. “The largest percentage of money managers cited client demand as their top motivation for pursuing ESG incorporation, while the largest number of institutional investors cited fulfilling mission and pursuing social benefit as their top motivations.” (We discuss the CEO letter penned by BlackRock Inc.’s Larry Fink on this topic in aprevious post.)

Skeptics argue that, by constraining portfolio choices, ESG investing must accept lower returns. Cynics mock what they call the Davos elite’s perceived commitment to corporate social responsibility, particularly when CEOs make 168 times as much as the median employee. Nonetheless, even if executives and investors don’t expect to single-handedly tackle climate change, this doesn’t mean that a focus on purpose is misplaced—particularly when the purpose is more narrowly defined the reason the corporation was founded in the first place.

“Big P” purpose and “little p” purpose

The Harvard Business School’s Joseph L. Bowers and Lynn S. Paine begin their article “The Error at the Heart of Corporate Leadership” (Harvard Business Review, May-June 2017) with the story of how “hedge fund activist” Bill Ackman attacked the board of Allergan, a pharmaceutical company, for its refusal to negotiate over an unsolicited bid by Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

“Ackman praised Valeant for its shareholder-friendly capital allocation, its shareholder-aligned executive compensation, and its avoidance of risky early-stage research. Using the same approach at Allergan, he told analysts, would create significant value for its shareholders. He cited Valeant’s plan to cut Allergan’s research budget by 90% as ‘really the opportunity.’ Valeant CEO Mike Pearson assured analysts that ‘all we care about is shareholder value.’”

Bower and Paine argue that the idea that a corporation exists to make money for its shareholders, and that the board should be willing to strip it of future growth potential if it can make a significant financial return now, is bad for the corporation and bad for the economy.

In particular, the focus on profits distorts management’s resource allocation decisions, which may cause them to miss greater expansion opportunities in the future. It justifies the hedge fund ‘playbook’ of buying a company in order to strip it down, selling off or closing less profitable parts and transferring the value to shareholders—and, generally speaking, this is not why people create companies. In their telling, the corporation is not a money-making “legal fiction” that should solely (or primarily) act as an agent for its owners; it is an entity in its own right with an interest in its own continuance.

Bower and Paine propose a company-centeredoperating model that identifies shareholders as just one constituency for which executives must create value, along with employees, business partners, and local communities. This framework implies a different strategic vision, different measures of success, and broader ethical standards. The leadership of a corporation must act as a fiduciary for all of its stakeholders, not just as an agent for carrying shareholder wishes—even defying a majority of stakeholders when their goals would not be in the best ongoing interests of the corporation. They write:

“Don’t misunderstand: We are capitalists to the core. We believe that widespread participation in the economy through the ownership of stock in publicly traded companies is important to the social fabric, and that strong protections for shareholders are essential. But the health of the economic system depends on getting the role of shareholders right. The agency model’s extreme version of shareholder centricity is flawed in its assumptions, confused as a matter of law, and damaging in practice. A better model would recognize the critical role of shareholders but also take seriously the idea that corporations are independent entities serving multiple purposes and endowed by law with the potential to endure over time.”

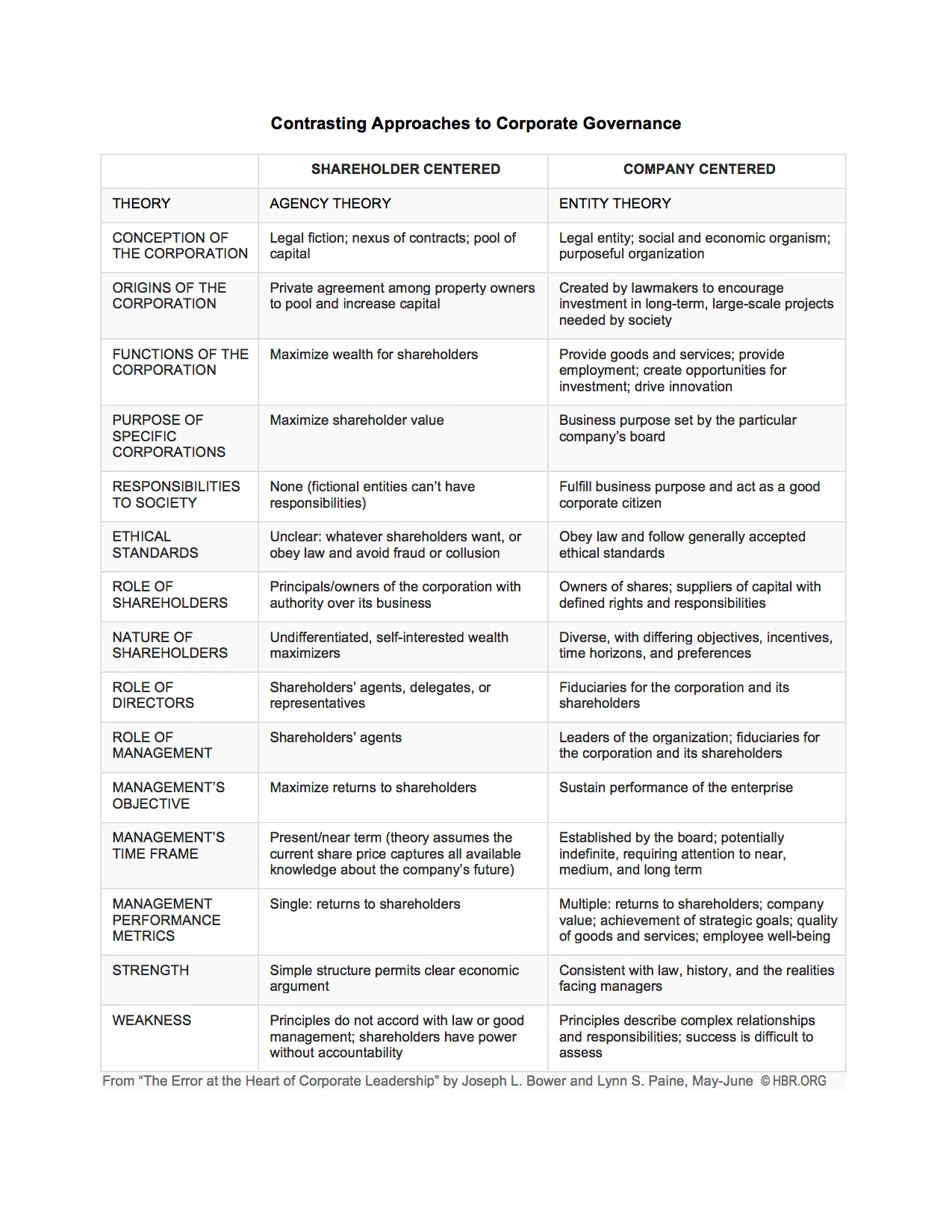

The graphic summarizes Bower and Paine’s company-centered model vs. the traditional shareholder-centered model: