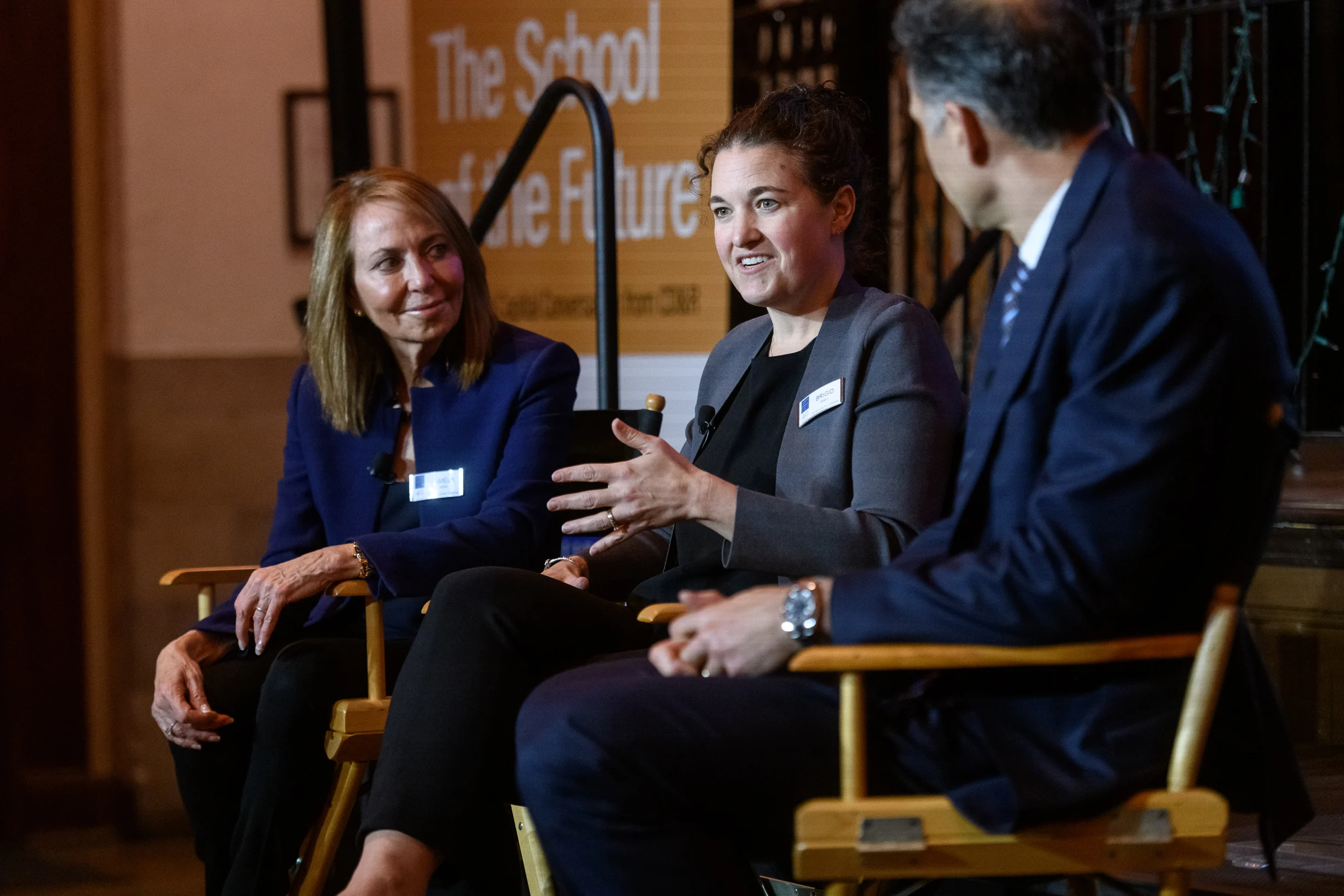

Following the recent presentation by Pamela Cantor, M.D., Founder and Senior Science Advisor of Turnaround for Children, on the School of the Future, CD&R Partner David Wasserman hosted a roundtable discussion with Dr. Cantor and Turnaround for Children CEO Brigid Ahern.

Following the recent presentation by Pamela Cantor, M.D., Founder and Senior Science Advisor of Turnaround for Children, on the School of the Future, CD&R Partner David Wasserman hosted a roundtable discussion with Dr. Cantor and Turnaround for Children CEO Brigid Ahern.

David Wasserman: That was fantastic. Thank you so much, Pam. I’m David Wasserman from CD&R. This is Brigid Ahern, who’s the CEO of Turnaround, and Pam, you’ve just heard from. We’re going to take 15 to 20 minutes just to talk about follow-up on Pam’s remarks there.

I was thinking about, as Pam was talking, I have failed as a father because I have four kids and I never made them do the Marshmallow test, and I should have had each I them eat a frog and then none of them would have procrastinated.

I thought we would step back for a second, Brigid, and just talk about how the work and the Science and all that you’ve done fits into broader education reform. You’ve now been doing this for almost 20 years of field education, so that’s probably 2001, and that was the start of the Bush Administration. It was a big focus of that administration. It’s a focus standards and accountability and testing. Obviously, it was a big focus of the Obama Administration – Arne Duncan focused on education reform. There’s been a huge rise of charter schools.

So, as you think about that kind of arc of reform, yet there’s still this massive problem we have, this learning gap that you talked about. How do you feel? Like, the work that you’ve done around the Science and how children learn, and how Turnaround kind of fits into that whole context?

Dr. Pamela Cantor: The thing that education reform has been focused on during two administrations, Bush and Obama, had a great deal to do with a focus on accountability and the belief that the teacher was the most important factor in whether children would do well. So, let’s make great teachers, let’s have a great curriculum, and then let’s test kids.

So, what’s missing from that picture? The thing that is missing from that picture is that none of it took into account how children learn and the fact that all children have different developmental starting points.

A different developmental starting point might mean whether or not you went into a good preschool. It might have something to do with what you were exposed to as an only child. But, there’s an assumption in 20th Century education that every Kindergartner starts out in the same place. We don’t. We just don’t.

So, without an understanding of developmental variability, and designing classrooms for that variability, the obviously happens. The kids who are prepared do well. The kids who aren’t prepared, don’t.

Teachers can only make up so much of that delta. So, I think that what was missing from those eras, and I would be the last person to say that academic rigor and accountability is something we shouldn’t have; we absolutely have to have that. But, we really do have to design our classrooms for the variability that’s a truth in who is in our schools.

David Wasserman: Why is it that we often see greater variability in full poverty or hard-hit communities?

Dr. Pamela Cantor: I hope that the message in the talk that I gave enables you to see, even anatomically, when I talk to you about those three structures of the limbic system, the experience of adversity causes those three structures and influences the way they develop.

So, if you have focus here and memory here and stress here, if this one is lighter than the other two, then it’s very difficult for children to focus, to pay attention, to control their behavior. We have treated the classrooms that have poverty kids as if this was not true.

It’s not that it’s not solvable, it’s absolutely solvable, but we can’t pretend that it isn’t there. These children are coming in with a lot of struggle. When I was- 2001- walking into schools, I’m thinking, ‘Don’t they see what’s going on here?’. It was very strange for me, because I had 20 years of practice with kids before that, that was before insight.

David Wasserman: Brigid you have, you joined Turnaround for Children five, six, seven years ago. Before that, you worked for the city in education, and before that you worked in a non profit focus on charter school, right?

I want to go back to the first question that I asked Pam about you know it’s kind of hard from an educational performance… I’m just curious from your point of view how seeing the different things you’ve seen and how sitting in the seat you’ve set, do you agree with kind of what’s missing, and from your experiences in trying to form education as a charter school person in the city here?

Brigid Ahern: Yes, without a doubt. You know what’s interesting, so when I, I worked at the New York City Dept. of Education, and I went to Uncommon Schools you know to Turnaround. And even in our work right now, so what Turnaround does with everything that Pam just mentioned is we translate insights from sciences into practices in schools that can be used in real school settings.

When you look at, where most kids go to school is district schools. So, there’s a change management process in both, but it’s really different. In districts there are vast resources, so many weapons for change, but it’s very complex, very fragmented.

But, there’s a huge opportunity there, and we work with district, and public school, and have seen that you can really vertically integrate, and get results by working with the system of the schools and the readers directly. Charters are different. They’re for the most part really highly operational systems, but it’s a different challenge because healthy development is not something that you can pick and choose off of a menu. You actually have to do it in an integrated way.

And so, you are working with a system that’s already in place, but when we go to kid dc, we work with they’re gobbling it up. It’s just how do we actually work it into their system to make it happen. So, what’s really remarkable though is that we’ve made it work with districts, with charters. And there are so many other organizations that have potential to prep work as Pam was mentioning.

Teachers potentially not even being prepared or knowing about the science to be able to apply it in the classroom, so there’s so much opportunity I think for what we have.

David Wasserman: Well obviously as a teacher, so you know you said there was a lot of emphasis on teachers in the Obama administration, but now it feels like you guys feel like there’s a new set of learnings that teachers don’t necessarily get at teacher colleges, or even maybe decent charter systems, and in their everyday job teaching in districts. Can you give us a little bit more flavor of what that is? What you feel like based on the science that you’ve studied that they’re missing?

Dr. Pamela Cantor: I have one story. District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) is a new system in the district. Much, much less big than we were. You have to get your arms around it. But as a chancellor, Kaya Henderson, who’s a superb instructional leader, made an enormous investment in the instruction side of the house.

So, that her teachers were really, really prepared on the academic content. But they didn’t have our content. They didn’t have content on science, on skill development. They didn’t have that stuff. So what do you think is happening right now? We have this partnership with DCPS intensely vertically integrated. The academics are strong.

And what’s happening is they’re getting outside gains in schools that can never get outside gains before. Because they’re putting pieces of the puzzle together. The point I wanted you most to take away from whole child personalization is we cannot do just one thing. We will miss to many kids.

David Wasserman: [On personalized learning, you can get a] whole picture of building a house. Until you do the foundation you can’t build the first level, you can’t build the second level, and same thing with a student: Until they master one level of math, they can’t do the next level of math.

Tell us what, so that’s one level of personalized learning. Tell us what whole child personalized learning is.

Dr. Pamela Cantor: So, the things that were in that time were very powerfully in tune with what the science says. So one thing all of you can just understand logically is that if a teacher is in a classroom with 35 kids and is talking from the front of the room, relationship isn’t there.

A relationship is something that you have to design a classroom to be able to do, because teachers have no time for relationships. So we have practices that we give teachers that enable them to make connections with kids in all kinds of different ways. To get that particular electrical emotional thing going on.

I mentioned Kaya and the rich instructional environment of these schools, so lets assume for a moment that’s covered. Probably not, but it’s covered reasonably well. But then these schools are not always safe. So you can have these incredible resources, but if a child like Thomas doesn’t feel safe walking into school, because of gangs on the block and all of that stuff. So that’s not good.

The intentional development of skills and mindsets has been completely absent from teacher training and completely absent from the equation. How can you have an education system that doesn’t develop the skills and learning? It just makes no sense. But when you put these pieces together and you say relationship, safety, rich instructional experiences, skills and mindsets, then you begin to see how the pieces fit together.

The technology is an incredible asset to us, because it can free teachers to be able to do the things that normal humans can do.

David Wasserman: Brigid, I want to come back to you because I think a lot of us here are in business, so it’s, we all know that culture means a big deal for the businesses we run, but that’s kind of the hardest thing to do. Like how do you go and create a culture. How do you, and one of the things you guys are trying to do at schools, is you’re trying to create, help the teachers and principles create the culture that allows… and the trust, and all the things you were talking about.

And to let children learn a different way. Tell us a little bit about the challenge of trying to operationalize that? Because that’s a hard thing to do. It’s a hard thing to do in a business where you’re dealing with, you know with 30, 40, 50 year old adults who have already been educated seems like a much harder thing to do in a school where we have all the complexities of that system. I know it’s an unfair question.

Brigid Ahern: So, the way I would think about it is that leaders have an unbelievable opportunity to create the school environment that Pam just talked about. But what we’ve found is that when leaders understand the why behind it, how do children develop as learners? What does context do for the developing brain? That they have, it’s almost liberating in some way.

Because they suddenly understand what they didn’t understand to begin with, and then all of these other pieces can fit into place. And so one of the things that we do, I mean what Pam said at our talk is that we want schools to be a powerful developmental force in a child’s life. And that’s why leaders and teachers got into this business in the first place.

So, if we can make that easy, if we can translate it into tools, and strategies like the frog strategy, these are not always complex things, right? But if you can train leaders to do this and work together, in an integrated way in a school setting, they see the affects that has and it doesn’t just affect the student’s in the school it affects the teachers.

Because, they are suddenly able to do the work of their lives in a way that they weren’t able to before, and so one of our, our theory of action is about training leaders on the science of learning and development, and then what they can actually go do about it, and then we support and help them. We do the internal assessments so they can see what’s right in their culture right now.

What should they prioritize for a second and third? And then how do they actually go in and a lot of schools in the system can get it done, but what we’ve seen is just how invigorating it is for leaders to be able to go in and make those changes, and see the affect that it has on learning.

David Wasserman: That reminds me in the business world, you know we used to always manage the output, and focus on the output. And if you think about a lot of readers today they tend to focus more on: How do you create a culture to perform? How do you create a diverse environment that allows the output to happen?

Instead of just trying, I think there’s a parallel to it with the business world with what’s happening in the education. You know where you said Pam a lot of the pro education form was a lot like business was 15, 20 years ago. Let’s just measure sales. Let’s hold people accountable. Let’s be a really hard ass CEO, right?

I think you see that change happening in the business community as well, right? People will call it the most valuable companies in our country today. They attempt to be very innovative companies, and they tend to focus on input as much as output. How do you create the right culture?

Dr. Pamela Cantor: Well what interests me in that right now is that, I have been very struck by a difference between medicine and education. In medicine if you were working with a child, and you just decided to fix the problem that the child came in with so they have a better life. You never ask another thing about that child, right? You just, they’re a number to you. That has to get fixed.

The doctors are trained not to do that. You’re trained to need to know a certain set of things, and you’re training in that set of things, but you have to know about that child in order to give that child love. Even if it’s a broken arm.

In education there are all these binary questions. Like if you’re into social and emotional stuff, it means you’re not into rigor. You don’t care about academics, and I don’t understand why, we are asked to make these binary choices when it’s the synergy between these things that is actually going to get it done.

So, that idea of hard ass CEO, or hard ass principal, I mean every hard ass principal we’ve ever seen, everybody’s working around that principal and nothings getting done. I mean we see it all the time.

David Wasserman: I think the way the world of health care today you see a big focus on public health in the same way. Let’s not just fix the disease, let’s figure what it takes to make people healthy? My guess is those parallels are the same. Let’s take some questions from the audience…

Audience Question: You talked about contact and activity and medication, so there’s food or other questions. Is that a thing you spent time on? How do you think about other factors besides trauma or stress that could be impacting our children?

Dr. Pamela Cantor: I think you are raising an important one, which is nutrition is huge, and the chemical effects on the body from things that are well known. Sugar, fermented foods, many of these things are very real. They haven’t been as interesting to the medical profession until recently. So I think there’s a lot of really interesting work going on right now about that.

There’s also some really interesting work on about sleep. So as an example one of the most interesting studies about sleep would suggest that they adolescence school day should not start until 11 in the morning. Because of the nature of the way their circadian rhythms are. And that they will give greater focus, greater attention, greater concentration if we just started the school day at 11.

Well, people are not starting the school day at 11. There are many open and willing to really use science. If we really were open to it then we would have to understand the diet, processed foods, and when the like do have effects just like the stress that I was talking about. But other constitutional factors like sleep matter as well.

Audience Question: Your philosophy is very compelling, but I have a few concerns with it. What is this information of a young generation of getting a participation trophy just for showing up? And the second one is to those people who are brought up in this context fight, how do they react to the boss [who is not nurturing in a positive way under that pressure]?

Dr. Pamela Cantor: I think that there’s a counter thread in the question that relates to the issue of calibration, of discomfort. I think on the subject of trophies for showing up, I just think that’s a total disservice to children. It doesn’t enable them to build skills, mindsets, habits if they don’t know how to lose. If they don’t know how to fail.

And teaching failure, and teaching what failure can mean to growth is one of the best things that any adult can do for a child. But, there is such a thing as calibration in the ways that children are allowed to fail, and who is talking to them at that moment of failure?

Is it a person whose voice conveys get back up and try again or tells a story about something that happened to them? But the point of the adult at that moment is to get them back up again. And to get them to try again. The other one you were talking about I also think is an issue of calibration, because if children do develop the kinds of skills, mindsets, and habits that I was talking about, they’re resilient.

They are not going to fold if somebody isn’t like their mom, their dad, or their best teacher. I think if you look in your life at those that nurtured you, one of the things that nurturers gave you was the ability to sustain yourself during those difficult times. But I think what both of these things have in common is that the responsibility of the adult is to prepare the child for life.

Audience Question: If the saying “don’t shoot the messenger “is probably thrown around for a reason. That people often, rather they create a protection, which is often just sort of a self confidence. Just stands in the way of learning failure. I understand what you’re saying, but I worry to take my own.. to school, but I’m trying to worry about sales. How are you that person who’s nurturing, and tell us during that whole failure that there is a truth behind that failure, and that you should get up and dust yourself off, and do it in a positive nurturing way? And still the person responds to you positively for being the messenger or waking you up to the fact that the person was not in hindsight for a negative reality has a point?

Dr. Pamela Cantor: Let’s look at this as a triangle where you’re the dad, and your child is saying to you something that an adult said to them that was critical of the behavior or result. One option that you have is to soothe and comfort and all of that. Tell them that they’re still the greatest kid in the world.

But the other possibility is to extract the truth that the child at that moment can’t see, because they’re just in too much pain, and that sentence goes something like this person might have done you the biggest favor in the world. Let me tell you why. Then if children believe that they’re not the only one to whom this happened. Especially if they’re teenagers, that’s really helpful.

Because when you think it’s just you that’s the loser, I hate to use that word these days, but, that’s really painful. So, giving a child a sense that you will always tell them the truth in what’s happening. You’re never going to pussyfoot around that, but you’re also going to do something that enables them to cope and grow.

David Wasserman: Pam, Brigid – thank you for joining us and leading this excellent discussion and presentation on the School of the Future.