In today’s workforce, business leaders select managers based on their successful track record of a certain field. By achieving in a performance-based role, employees pave the way for a new measure of responsibility – managing a team of their own. Although this professional trajectory seems intuitive, it fails to account for the different skillsets required of high performers and strong managers. However, it’s important to remember, that if someone is becoming a new manager, then they need to have the proper training and skills needed to be successful, you can check out this article about managers and mentors and how this can benefit you and your business more. Making sure that your new manager is fit for the role, is a key component for any business to be successful.

Gallup concluded in their State of the American Manager Report that 35% of managers are engaged with their jobs and only 18% have “the high talent required of their role.” They estimate that miscast managers cost U.S. economy $319 billion to $398 billion annually because of their failure to motivate employees. Gallup summarized the issue behind the statistics as follows:

“As Gallup has found, companies repeatedly put people in manager roles because they were successful in previous roles or because they have been with the company for a long time. This is a flawed strategy with serious consequences for an organization’s engagement, financial performance and long-term sustainability. Organizations should be highly conscientious in their succession planning. A great front-line employee is not necessarily going to be a great manager, and a great manager is not necessarily going to be a great leader. Each of these roles requires a different set of talents.”

David Brendel, an executive consultant and Harvard Business Review contributor agrees. Brendel has found that this “fundamentally flawed” approach to management “rears its head in virtually every business and organization.” But unlike Gallup’s report, which states that only 10% of individuals exhibit the natural talent for management, Brendel offers a simple behavioral solution that makes “failure rare” among thoughtful leaders.

Brendel believes that first-time managers need to embody “leadership behaviors” immediately, adopting verbal and nonverbal communication that garners respect while appearing “supportive and collegial.” Instead of buckling under the weight of shifted expectations, Brendel recommends that first-time managers prioritize a simple practice: “ask open-ended questions and avoid making directive statements.” Specifically, Brendel found that high-performing managers keep a ratio of 10 to 1 between open-ended questions and directive statements.

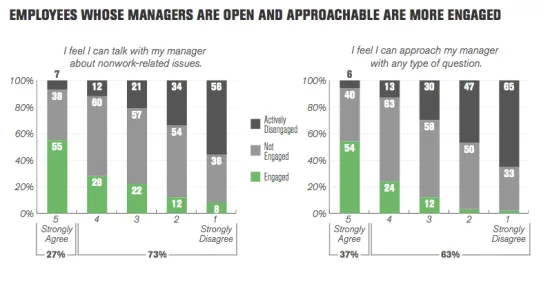

When delivered in a calm, intentional way, open-ended questions offer development opportunities to employees while giving a new manager valuable information about the “motivation and adaptability” of their team. Questions also foster trust between direct reports and new managers, implying that leaders value the opinions of employees. For a positive transition from an operational to management role, “ask good questions, listen carefully to the replies, and facilitate dialogue.”